Well, it’s been quite a while, but I am finally getting back into writing about the First World War. To start with, to allow for my schedule, I’ll be posting every other week, most likely on a Saturday. But as time goes on, this may well bump up to once a week. Regardless, I am looking forward to getting back to writing and sharing stories with you all.

There are truly so many topics that could be covered, there’s almost too many to choose from. So, to restart my posts, I have chosen a topic I am passionate about – the lives of the men of Rowley Regis/Blackheath and Old Hill who died as a result of the First World War.

Back in 2020, when COVID was busy turning our lives upside down, I decided to undertake a local passion project – to visit all the burial/commemoration sites of the men from the area of Rowley Regis/Blackheath and Old Hill who died in the war. This started with defining the boundaries of the area where I would research as these three separate towns during the war have now merged as part of the wider West Midlands conurbation. I also took in the names that were commemorated on the various memorials scattered throughout the research area and undertook thorough searches of the 1911 census and servicemen’s pension records.

After four years of working on this database, I have found 411 men who fit the criteria I have set. Of those I have researched 408, with three proving completely elusive due to limited information available. The spread of deaths across the years of the conflict are quite interesting – with 1917 being the worse for this area with 122 deaths. 1918 then follows closely with 113. There’s also a broad spectrum of men who are killed, with no real patterns displaying themselves. If anything, it is a good cross section of the society of the time. The average age of those killed (for those we have data for) is 24.5 years old; we’ve got 30 sets of 2 brothers, 3 sets of 3 brothers, and even a set of 2 cousins and their uncle. There’s a variety of jobs – from coal miners and teachers to bricklayers and soldiers.

Of the 411, I have currently visited (or have had people visit on my behalf) 215 and am planning trips to areas where I have a substantial number of men to visit. Some of these will be tricky or potentially even impossible – like the 7 who are commemorated in Iran or Iraq. Over the last four years, I feel I have come to understand and know these men very well. The lives they lived, the families they had, the jobs they worked in the run up to the war and I would like to share them with you. Over the course of a few separate blog posts, I will introduce you to just a handful of the men I have researched and the lives they had – in this first post, I will share the stories of four men.

The first of the four is Lance Corporal Samuel Roper DCM. A prewar nut and bolt labourer, Samuel arrived in France on 31st March 1915 as a member of 1st/7th Worcestershire Regiment. He was married to Elizabeth and had a daughter called Annie born in Nov 1912. In 1916, Private Roper was involved in an incident which would see him awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, or the DCM. From what I can deduce, based off when Pte Roper received his medal in the field on 10th September, and when the award was gazetted on 28th September, I believe he undertook his action sometime in the late spring/early summer of 1916 – it’s hard to find the exact date. His citation for his DCM reads as follows:

‘For conspicuous gallantry in action. He used his machine gun with great effect during the attack, and, when another platoon was being driven back from an attack on another point, and artillery fire. He carried out his instructions with the greatest courage and coolness under intense fire.’

At some point between 10th September and 13th November 1916, Private Roper was also promoted to Lance Corporal. We know this due to the fact that on 13th November, Samuel Roper dies, and is recorded as Lance Corporal at that point. L/Cpl Roper’s unit were undertaking duties on working parties at the time of his death and he is buried in Contalmaison Chateau Cemetery. He has no inscription on his headstone and was 22 years old.

The second man featured today is Corporal Albert Harrold of 5th Bn Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. According to the 1911 census, he and his family were living at 132 Bell End, Rowley Regis and before the war, he had worked as a clerk in the council offices of Old Hill and had become a commercial traveller for Brook Tool Manufacturing Company in Birmingham. He was also a member of the Blackheath Male Voice Choir and an amateur footballer for the Rowley Associates. According to his medal card, Corporal Harrold landed in France on 20th May 1915.

Albert only managed just over four months in the trenches before being killed in his battalion’s attack near Bellewaerde Farm on 25th September 1915. Before his death, Albert wrote his last letter home to his wife, who decided it should be published in the local newspaper; and it read as follows:

‘I am writing this letter hoping it will not be necessary to forward it and leaving it to someone to post only when they have certain news that I am dead or missing. During the next few days, we shall be very fortunate indeed if we are neither killed nor injured. There is a big attack coming on, and my battalion is in the first line. Our orders are to take two lines of trenches. So, you see they cannot be carried without risk.

In addition, prior to the attack, a mine is being exploded within a few hundred yards; we shall be lying out in the open and this will cause many weighty things to be flying about in close proximity to us. Then there are the bombardment, the holding of the trenches, if captured, and possibly a counterattack. Altogether it is odds that a few of us will stop something. I hope you will not get this letter, but if you do, remember that my last thought was with you.’

Albert Harrold was one of the 474 casualties (killed, wounded, missing, prisoner) the 5th battalion lost on that day. He is also one of those whose body has never been found and he is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ypres. He was 33 years old and left behind a widow Sarah, and four children – Irene, Daisy, William and Frederick.

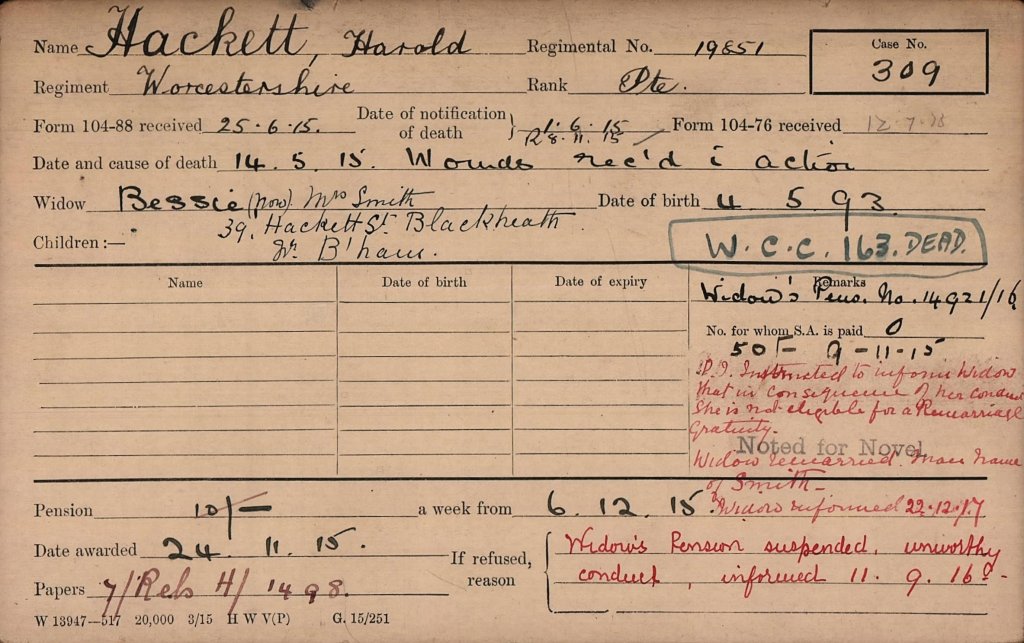

The third man to be featured today is Private Harold Hackett. Before the war, he had been a labourer at the steelworks at Langley Forge and had been married since August 1912 to Bessie Painter. Harold had only arrived in France on 22nd April 1915 and was immediately sent to his unit, 2nd Bn Worcestershire Regiment, where he was wounded just three weeks later on 14th May 1915, subsequently dying of those wounds. He was 23 years old and is buried in Bethune Town Cemetery.

But it is what happens after Harold’s death that’s interesting. On his pension card, his widow Bessie is shown as the beneficiary. The first thing that’s noticeable, is the fact that she has remarried and is now Mrs Bessie Smith. Now this in itself is not unusual. Many women remarried after they were widowed during the First World War for a variety of reasons. Simply, for love maybe. Possibly for security – having a man around the house who could provide for them and any children they may have had.

But it is what’s written on the right hand side of the pension record that is intriguing. Two separate comments which are written in red pen and noticeably different from everything else on the document: ‘Widows Pension suspended, unworthy conduct, informed 11/09/16’ and ‘Instructed to inform widow that in consequence of her conduct she is not eligible for a remarriage gratuity. Widow informed 22/12/1917’. According to the Memorandum for the information of Widows of Officers and Warrant Officers placed on the Pension list (there is an equivalent list for enlisted men) point number 8 discusses ‘Unworthy Conduct’ and states ‘A widow’s pension may be suspended or cancelled by the Army Council by the Army Council, if the widow should prove unworthy of the award.’ There doesn’t appear to be any further indication of what might have warranted such a response towards Bessie. Some examples that I found of those who had their pensions revoked were due to criminal activities, unbecoming behaviour post death of their husbands, or even extra-marital affairs whilst their husband was still alive and serving overseas. But it does highlight the complexities of wider society at the time and what those at home might have been experiencing themselves.

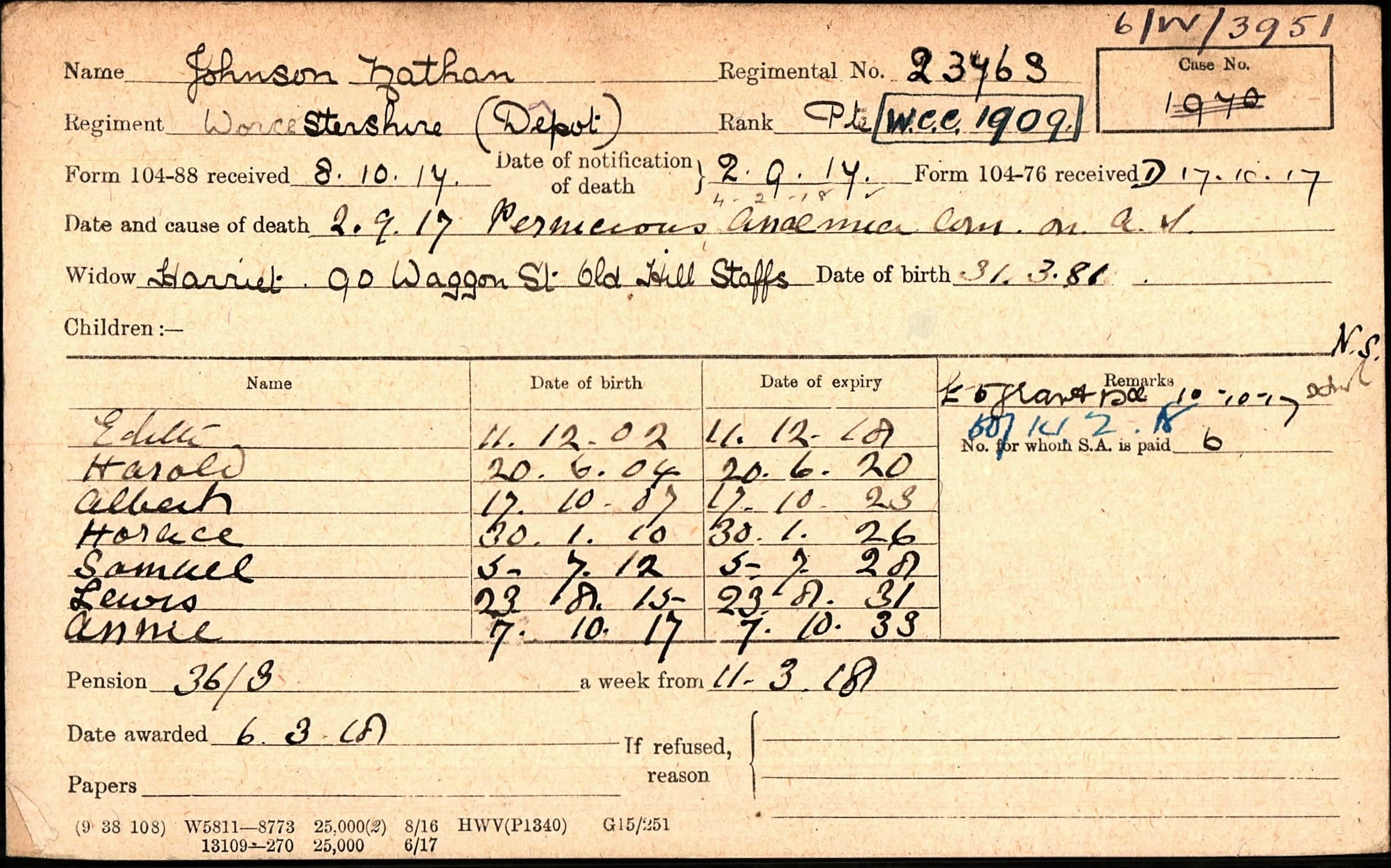

The final man I will cover today displays the fact that not everyone who died in the First World War died as a result of some great advance, or injury. Private Nathan Johnson of 4th Bn Worcestershire Regiment died on 2nd September 1917 and is commemorated in Cradley Heath (St Luke) Churchyard. But Pte Johnson didn’t die as a result of wounds. He is one of those who died of disease but still is classed as a casualty of the First World War – dying of Pernicious Anaemia. At the time of his death, Nathan was 38 years old and heartbreakingly left behind not just his widow Harriet, but seven children – Edith, Harold, Albert, Horace, Samuel, Lewis and Annie, who was born 5 weeks after her father’s death. Pte Johnson’s grave has since been lost and is commemorated, along with others, on a special memorial.

There are many more stories to tell from Blackheath/Rowley Regis and Old Hill – with new ones still making themselves known, 4 years into this project – and I look forward to sharing a handful more with you in the future. Ideally, I would one day like to advance this research, maybe into a book, so keep an eye out for future details!

Hello Beth I have really enjoyed reading your post this morning – You really can’t believe how brave these young soldiers were & their families –

thank you so much for e-mailing me your wonderful research concerning such a important & topic which should always be remembered

Love & best wishes to you ,John. & family

Carole xx

LikeLike