When I’m out guiding the battlefields of the Western Front, I usually end up covering the same areas of Ypres, the Somme and Arras. Whilst these are always important to visit, particularly for a novice battlefield tourist, there are so many other locations that are just as fascinating and worth of visiting. In this post, I am going to write about one such place, a location I had never visited before COVID, but have come to study and understand in far greater detail and the anniversary of which will be happening in the next week.

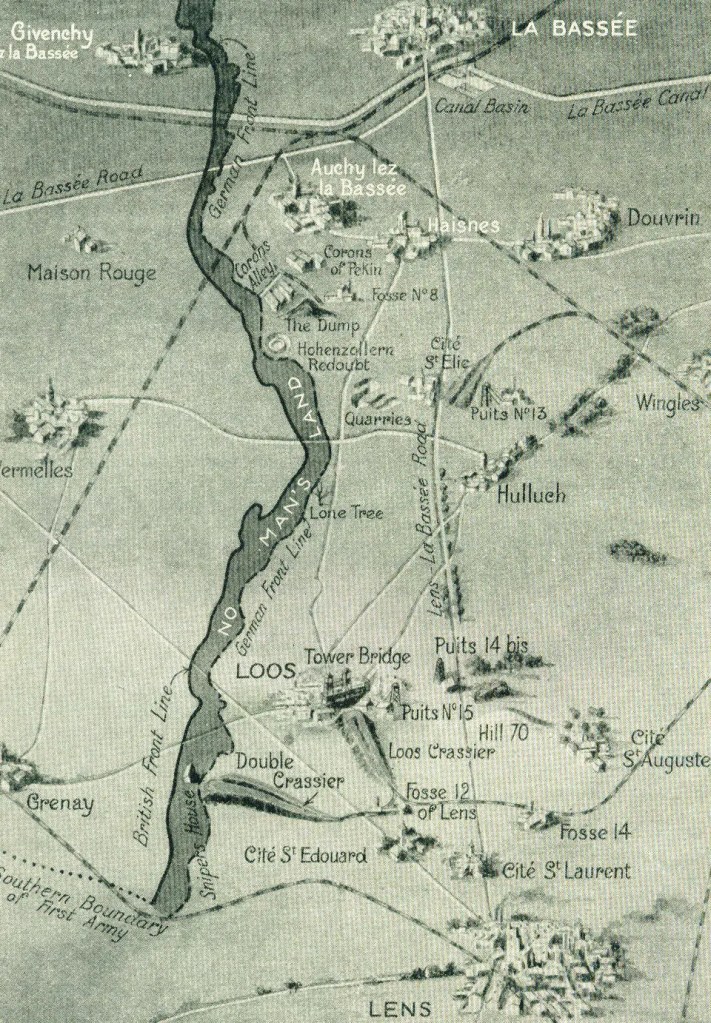

25 minutes north of the city of Arras and on the outskirts of the city of Lens, there lies a village called Loos-en-Gohelle. Historically a heavy mining and industrial area, with slagheaps dominating a flat landscape, the village and those surrounding it were at the heart of a major offensive in September and October 1915 – the Battle of Loos. Even though it was a supporting offensive for the more extensive French Third Battle of Artois, this battle can be considered the first truly large-scale offensive carried out by the British, earning the moniker at the time of ‘The Big Push’ and is notable for being the first time the British used Chlorine Gas as a weapon. Whilst carried out on a ground not of their choice, and right in the heart of the 1915 Munitions crisis, the best of a difficult situation was made and on the first day of the attack – 25th September – there were some breakthroughs made. Some other particularly key dates in the battle were the 8th and 13th October, but the fighting was sustained over the whole period. The offensive lasted for almost three weeks with more than 60000 British casualties.

If you’re looking to take a trip around this often-overlooked battlefield with the 1915 battle as a focus (there are plenty of things to look out for from a 1917 perspective), there are several sites I would recommend visiting. Of course, there’s always more to discover, and plenty others I could have included in this list, but this would be a good introduction to the area and give you a taster of the kind of places you can explore!

Whilst there is no set order to visiting these sites, a good starting point would be the village of Vermelles. Sitting right in the heart of the 1915 battlefields and just ¾ of a mile from the British front line, the village would have been a place well known to those in the trenches nearby and is regularly seen in photographs taken during the Battle of Loos.

Another location that can be visited is the cluster of three cemeteries which all show different types of burial and commemoration – St Mary’s ADS, Bois Carré and Ninth Avenue. These three cemeteries are interesting as they all show different methods of burials from the war. The first is the location of an Advance Dressing Station called St Mary’s, which was set up during the battle and after the war, a cemetery was created there. This type of cemetery is a concentration cemetery – meaning that graves from across the battlefield were brought there later. The majority buried here are casualties from September and October 1915 but there are burials here from other times, most particularly Canadians killed in August 1917 whilst attacking Hill 70 nearby. There are over 1800 burials here, of which around 220 are identified. In this cemetery, is commemorated Lt Jack Kipling, the son of Rudyard. His identification in the 1990’s is potentially controversial, with some believing that it is not Jack buried in that grave. However, the evidence presented at the time was convincing enough for the authorities to accept that it was him. I will be writing a further blog post in the coming weeks about Jack, his life and his commemoration.

The second, just behind St Mary’s ADS, is Ninth Avenue Cemetery. This is what is called a battlefield cemetery, one that was created during the war and is still in the same location. This cemetery was named after a trench of the same name that ran through the area. It is an uncommon type of cemetery as the majority of those buried here were buried in what is essentially a mass grave. These men were brought here after the battle was over. The front lines had moved forward and parts of the land behind had their uses changed, including being used for burial sites. There are 46 burials here, and those who were buried in the communal grave have headstones commemorating them plotted around the edges of the cemetery.

The third site, just behind Ninth Avenue is Bois Carré Cemetery, which was named after a wood close to the site. This is an example of another battlefield cemetery. It was created in the immediate aftermath of the first day of the battle, which is reflected in the units that are represented here – men of the Gloucestershire and Berkshire Regiments who attacked across the fields on this section of the battlefield on 25th September. The cemetery, as it was near to the front line was still used throughout the war including many Irish soldiers buried in 1916, including some infantry soldiers attached to tunnelling companies. There are 228 burials, of which 54 are unidentified and 47 are commemorated on special memorials due to their graves being disturbed during the war.

To really get an idea of the terrain of this battlefield and the impact that had on the fighting here, you really need to be standing on the ground itself. There are many places you can do this from – the Lone Tree and Le Rutoir Farm are two examples – but I like to walk the ground around the Hohenzollern Redoubt. To the northeast of Vermelles, this redoubt – a heavily defended German position which even today still dominates the surrounding fields – was a key location on this battlefield that required taking control of. It was originally taken by 9th (Scottish) Division at the end of September but was lost on 8th October during a German counterattack. The 46th (North Midland) Division were then tasked with retaking this vital strongpoint. I won’t detail what happens during this attack here as I have already written about this attack on another post – to find out more, read this post here.

This location really is a key site in understanding the topography and how that impacts the choices made by the British and the Germans of where and how to build defences, trenches and so on. You can see this additionally from Quarry Cemetery, a short walk from the redoubt. Seen on the left-hand side of the map above, sitting just behind the front line, this quarry was used as a burial site from June 1915 – another example of a battlefield cemetery. There are over 100 burials in this cemetery – with 10 unidentified and many headstones that also have the words of ‘Buried near this spot’ upon them. This includes one Fergus Bowes-Lyon, an elder brother of the Queen Mother. Originally noted as missing on the Loos Memorial, evidence of Fergus’ burial somewhere in the quarry was accepted in 2012.

Finally, no visit to the Loos Battlefields would be complete without stopped at Dud Corner Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing. Sitting on the top of the ridge on the Lens-Bethune Road, near to the site of the Lens Road Redoubt, “Dud Corner” Cemetery – believed to be named after a large pile of unexploded shells found in the area after the end of the war – there are nearly 2000 burials here, of which over half are unidentified. There are two Victoria Cross winners buried here. Surrounding the cemetery is the Loos Memorial which commemorates over 20,000 men who fell on the battlefields between the River Lys and Grenay during the First World War and have no known grave. What makes this site unique is that there is a viewing platform built into the cemetery, which allows the viewer access over the cemetery and memorial and gives a bird’s eye view across the whole 1915 battlefields. If there is one place that must be seen whilst in Loos, it is definitely this one.

As I mentioned in the introduction, there are a number of different locations that could have been included in this post – Le Rutoir Farm, the Lone Tree, Loos British Cemetery, Hulluch, Auchy Les Mines just as some examples – but the places above will certainly give you a great start on visiting Loos.